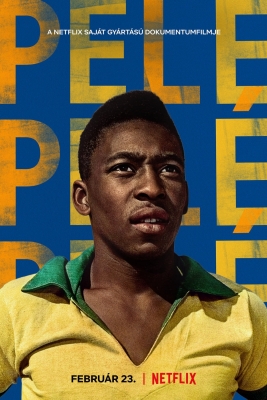

Pele (biographical documentary film); Direction: David Tryhorn and Ben Nicholas; Rating: * * * and 1/2 (three and a half stars)

BY VINAYAK CHAKRAVORTY

Football has forever blended deeply with Brazil’s socio-politics and culture, and if there is an icon who continues to represent the sport stronger than anyone else in that nation, it is Pele.

The idea is recurrent in David Tryhorn and Ben Nicholas’ new documentary film on the living legend, which tries understanding Pele beyond his footballing genius, in the context of what he and his craft has meant to Brazil of his times and thereafter.

Importantly, the film tries drawing a direct link between the popularity of sports and sporting hero, and how a dictatorial regime might use these to its advantage.

Tryhorn and Nicholas try summarising Pele as a fascinating bundle of ironies.

As the film opens, Pele is playing his last World Cup — Mexico 1970.He is on the brink of making history, having won the trophy twice before — in 1958 and 1962.

He is a footballing God already, to Brazil and world.Yet, as the Cup gets underway, like a mere mortal who needs security, Pele is “hidden away”.

There have been “plans to kidnap him and assassinate him”.

Showcasing the humane side of demigods is a convenient way to attract audience attention, and the makers use the formula liberally.

In an interview for this docu-film, an aged Pele arrives with the support of a walker.For maximum impact, the camera pans from behind, to give you the impression he is just another old man hobbling across to his chair before suddenly zooming onto his face.

The scene contrasts the magical vignettes of Pele of his heydays on the pitch, fleetfooted and agile, dodging and scoring at will.

The interview itself is not quite the best you’d see of a sporting superstar.

Pele doesn’t seem too interested, speaking in Portuguese with a frown that sits almost permanently on his face.May be, he had said it all over the years and has nothing new to add.

The 108-minute biography does a fine job in drawing up a portrait of Pele as a legend while depicting the mortal beneath the marvel.The tack, though is one frequently used in biopics.

For the sake of a fresh approach, perhaps, Tryhorn and Nicholas attempt to fuse Brazilian politics of the era with the story of Pele.

Early on, Pele describes the Brazil he was born in as “a country that was young back then”.

Given his underprivileged background he confesses not knowing much about the rest of the world as a child.During his growing up years, he assumed the place where he existed was the most beautiful in the world.

The innocence, the candour of the confession is in contrast to a very different facet of his country that would soon find mention in the narrative, one that was far from beautiful.The film mentions the military coup in Brazil of the sixties.

It had an impact on Pele as a celebrity, as a representative of his nation before the world.

For, the documentary seems to state a lot of Brazil’s footballing glory in the era of Pele had a correlation with state-sponsored propaganda.

The film touches upon the dark side of totalitarian Brazilian politics of that era, and the film makes the indirect assertion that the country’s military leader Emilio Medici maintained a ‘nice guy’ image in public by being spotted at football matches.Pele himself chooses to be non-committal when asked about torture, censorship, killings that had practically become institutionalised in the sixties.

“My father said football is for those who have guts,” he says early on in the film.Perhaps, to voice opinion back in Brazil of the sixties, mere guts wouldn’t suffice — not even if you were Pele, and that’s what the film is telling you.

Beyind politics, for football buffs and Pele lovers Tryhorn and Nicholas lay out the expected engaging spread.Black-and-white to colour clips of Pele’s on-field action are used all through the narrative, along with interviews of family, friends and colleagues that enrich the screenplay.

We get a brief reckoner on his father Dondinho, a footballer and a big influence in his formative years (Pele recalls how he was convinced his father was the greatest player in the world).From his first World Cup, Sweden 1958, teammate Zagallo recalls Pele as “a skinny kid” showing “no pressure of playing World Cup”.

When the narrative takes us to Santos, the first major stop of his footballing journey, clubmates such as Dorval and Pepe open up on the boy they always knew would play for Brazil.

Cut to the bone, Tryhorn and Nicholas have scored while capturing the essential Pele, on and off the spotlight.

They are credible highlighting Pele as the hero Brazil needed to look up to, in the time of political unrest.They miss out on exploring the mind of the phenomenon in the way, say, Asif Kapadia’s docu-attempt Diego Maradona did in 2019.

Still, Tryhorn and Nicholas’ film is a brilliant effort